Preface

Preface to the 250 year history of Palatine Lodge No. 97. (Formerly known as Sea Captains' Lodge, No. 218)

The Beginnings of Freemasonry in Low Street,

Sunderland by the Sea, County Durham, England.

Written and compiled by W Bro C H M Culkin, PPJGW, PM in the Lodge

The first Grand Lodge, the Premier Grand Lodge (Moderns), was formed in 1717, and freemasonry became organised and grew from that time. However, in 1751 a rival Grand Lodge (Athols or Ancients) was formed because its members felt that the Premier Grand Lodge was making innovations and disregarding certain Landmarks, which they claimed, had been granted to them by Prince Edwin in ancient times.

In 1813 their differences were reconciled and The United Grand Lodge of England was formed.

The debates and conjecture as to where and how Freemasonry was started are numerous and varied but there appears to be an inclination in favour of the idea that it developed, in one form or another, from stonemasons.

This belief is perhaps not helped by the knowledge that Elias Ashmole is recorded as having been made a mason in 1646 by a company of men, said to be freemasons, but without any stonemasons being involved.

The statement below was made in 1907 when W Bro Watson, a schoolmaster and the then Secretary of this Lodge, compiled the history of the Lodge to celebrate its 150th Anniversary.

From time immemorial Freemasons were a body of Operative workmen, actually engaged in the construction of Public Edifices. Their introduction into England dates from about 674 AD when Benedict Biscop (628 A.D. to 690 A. D) brought from the continent, to assist in the erection and decoration of the Monastery at Monkwearmouth; Painters, Glaziers, Freemasons and Singers, and from that date many buildings were erected by men in companies, who were called 'Free' because they were at liberty to work in any part of England".

Monkwearmouth lies on the north side of the River Wear, Sunderland, England and the Venerable Bede spent virtually all of his illustrious life (673 A.D. to 735 A.D.) between the Monasteries of St Peter and St Paul at Jarrow. St Peter’s Church still stands there today, as the Parish Church, albeit with only a small amount of its original structure remaining.

The initial task in compiling the 250 year history of this ancient Sea Captains’/Palatine Lodge was to try to ascertain, as factually as possible, the beginnings of Freemasonry in Sunderland by the Sea which led to its formation in 1757.

In Vol.1,”Landmarks in Freemasonry”, Page 35 (Crowley’s Crew) W Bro Watson makes this observation:

Speculative Freemasonry as practised "locally "is traceable to the establishing of an iron manse - factory by Sir Ambrose Crowley of London, an enterprising genius, in the Low Street, Sunderland, in 1682, but the site not answering expectations the Works were transferred together with his Cyclopean Colony, to Swalwell in 1690.

During their sojourn in Sunderland, "Crowley's Crew", as his workmen were called, held their lodges, which they removed to Swalwell and subsequently to Gateshead on Tyne, and which is now known as the Industry Lodge, No 48, the oldest lodge in the Province.

However, it is apparent that the initial impetus towards speculative freemasonry, in this area, started in Sunderland as described above.

The History of Lodge of Industry No 48 compiled in 1911, also makes extensive comment on the activities of Ambrose Crowley and his Crew after they had left Sunderland in 1690, arriving first in Winlaton and then to Swalwell c.1707.

This history quotes W Bourne, the local historian who wrote the History of Ryton, that Joseph Laycock moved from Wetherby, in Yorkshire, to become the manager of the Crowley Works in the early part of the 18th Century. He joined Swalwell Lodge and in 1735 was appointed as the first Provincial Grand Master of Durham by Lord Crawford.

When Ambrose Crowley, a Quaker and model employer decided to build an ironworks in Low Street, Sunderland by the Sea, in 1682, he did so mainly to free himself of his reliance on his Midland suppliers and to further his ambitious plans for the expansion of his business interests.

From the facts assembled below it may be seen that the group of men, hired by the 24 year old Ironmaster to work in his Iron Works, could very well have started the series of events which culminated in the existence of Sea Captains’ Lodge.

Initially Crowley recruited a good number of Belgian Catholic workers from Liege and adjacent European areas because of their particular expertise in metal work. Almost certainly, given the circumstances of the times, these men would have been Hammermen Guild members.

Locally we learn that the last ‘Smiths’ Miracle Play’ had been performed at the Iron Works in Sunderland on 21st June1817 on St Eloy’s Day, which appears to bear out the previous paragraph’s assertion.

From Scottish and other sources we find that St. Eloy/St Eloi/Eligius was the Patron Saint of the Hammermens’ craft, which included all workers in metals throughout all of Europe.

We are not aware of how many Hammermen members there were at the start up of the Works; how many left in 1690 to go to Winlaton and then on to Swalwell around 1707; or how many original Crowley or local men, perhaps stayed behind in Sunderland, to carry on their ‘lodges’ and possibly take part in performing the traditional ‘Smiths’ Miracle Play’ on St Eligius day.

Certainly, by 1688 there were over 100 men employed making nails, which were then in great demand for shipbuilding.

(In later years Crowley made much of his fortune making restraining shackles etc. for the slave trade!)

Nor is it known whether Crowley brought stonemasons with him to build his works but it is quite probable that he did – he preferred self-sufficiency.

In the years after 1690, when possibly the bulk of Crowley’s Crew left Sunderland, and say prior to 1745, there are no records available as to what developments took place there. Were there enough members left to carry on “holding their lodges” or did the ‘lodges’ cease to exist?

We do not know, we can only speculate on events, which might have occurred, but we feel that it is germane to again note that the Smiths’ Miracle Play was held in Sunderland until 1817.

However, we do know of the existence of a lodge in Sunderland prior to 1745 and this is testified to by the minutes of the Marquis of Granby Lodge, Durham:

April 24th 1745

“Bro Bryan Stobart a mason made in Sunderland was admitted a member of this Lodge”

Dec 19th 1751

“Samuel Thompson being made a mason at a Lodge in Sunderland was admitted a member”.

Dec 27th 1751

“At the same Lodge Bro Robert Gibson, a member of the Lodge at Sunderland, now residing at the City of Durham, was, at his request and the unanimous consent of the Society, admitted a member”.

On 25th November 1755 King George/Phoenix Lodge was consecrated and 14 months afterwards Sea Captains’/Palatine Lodge was also consecrated on 14th January 1757– both being Moderns lodges warranted by the Marquis of Carnarvon. The members of Sunderland’s ‘Time Immemorial Lodge’ could well have supplied the nucleus of these two lodges – we are not aware of any other reasonable likelihood.

Having, hopefully, established a credible case for how freemasonry evolved in Sunderland, and given the antiquity and fame of Crowley’s Ironworks, it seemed reasonable to make enquiries in order to form a picture of its position, structure etc.

W Bro Will Logan source

His notes of 1905 tell us that the Ironworks building had been situated on Low Street at the bottom of Russell Street but as much of that area is now occupied by Sunderland University Campus would we find that the site was now built upon or was it still available for inspection?

Surtees source

The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham by Robert Surtees unfortunately makes no mention of the former ironworks building in the Sunderland section of his work. However, given that we were aware of W Bro Watson’s remarks about Benedict Biscop’s Monastery at Monkwearmouth the following footnote caught the eye:

It is evident that Malmesbury is mistaken in asserting that Benedict built a church on each bank, the one dedicated to St Peter, the other to St Paul. The latter is certainly Jarrow; and both still retain their original dedication.

On the face of it, this deduction is perfectly reasonable, and Surtees would have made his own translation of William of Malmesbury’s remarks. (These remarks were made in Malmesbury’s “Gesta Pontificum Anglorum” The Deeds of the Bishops of England, Ch 186, page 221).

The Venerable Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of England source

David Preest source

The very first full translation of Malmesbury’s work, from Latin to English, was made in 2002 by David Preest and he translated these particular remarks of Malmesbury’s as.

This Benedict bordered both banks of the River Wear, a not uncelebrated river of Northumbria, with two monasteries called after the Apostles Paul and Peter. United in love and obedience to their rule, the monasteries never quarrelled.

Preest adds a footnote.

William presumably never visited the north east (this is questionable). The monastery of St Peter at Monkwearmouth (or Wearmouth) founded c.673, does border the Wear, but the monastery of St Paul at Jarrow, founded c.681, is seven miles to the north on the banks of the Tyne.

You may note that Surtees says “church” whilst Preest says “monastery” but they both arrive at the same conclusion that Malmesbury is mistaken in his facts.

However, at that time, this did not appear to be a worthwhile road to go down.

Crowley sources

Looking now for any references to Ambrose Crowley and his Works the book named below came to our attention: -

‘The Law Book of the Crowley Ironworks’ by M W Flinn

Publications of the Surtees Society 1957

This is a remarkable work, edited by M W Flinn (deceased) from innumerable original manuscripts (property of the British Museum) and gives an insight into Crowley’s business methods, management skills and enlightened views on the welfare of his employees which were well in advance of his time. However, he did have informers and indeed informers of the informers in order to have his ‘Laws’ strictly applied.

Everything was reported and recorded in order to lessen waste, lessen pilfering and maximise profitability. There was a constant stream of such reports, by post to his office in London and an endless flow back of new orders, new and amended ‘laws’ and exhortations to greater efficiency.

Officials and workmen alike were afraid not to report any matter, which might be considered under their care in case others reported it.

Importantly, its value to this history lay in the fact that we now had the name of a distinguished author who intended to write a new book on the Crowleys and who had taken great pains to gather information on a world wide basis (Crowley had enjoyed corresponding throughout the world to individuals and to learned societies etc. and Flinn had explored this avenue of research extensively).

Flinn explains that, unfortunately, an individual had destroyed Crowley’s company records!

Also with the knowledge that the Ironworks were demolished in 1918 we could now compare maps produced on either side of that date in the Low Street/Russell Street area.

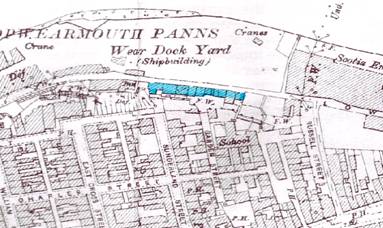

The results are shown below:

Fig 1

Map showing buildings prior to 1918 on south side of Low Street and west of Russell Street.

We are not aware which of these buildings were Crowleys.

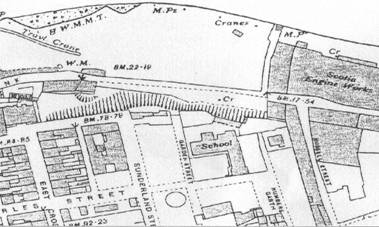

Fig 2

Map post 1918 showing buildings have gone.

Fig.3a, b and c

Russell Street from Low Street Retaining walls and buttress behind trees Foot of steep hill/cliff may have been at kerbside.

The series of photographs Fig.4 shows the details of the most probable site at the bottom of the cliffs.

(Given local co-operation a sample dig may find original foundations of Ironworks and small artefacts?)

Fig.4

Top of the cliffs showing the modern brick retaining wall in the background and the former foundations of slum clearance.

(Given local co-operation a sample dig may find original foundations of said Chapel?)

It was previously mentioned that in 1957 M W Flinn planned to write a book on the history of the Crowleys and their Iron business; he did so and named it: ‘Men of Iron, the Crowleys in the Early Iron Industry’ by M W Flinn, published in 1962 by Edinburgh University Publications.

(History, Philosophy and Economics No 14)

NB Edinburgh University Publications have a copy of ‘Men of Iron’ in their library but they hold no information with regard to his sources.

On page 40 of the above publication Michael Flinn, the author of many well researched and influential books and other articles informs us that a St Paul’s Chapel had once stood at this level which is possibly 70 feet or so above the Crowley site.

|

Author’s note: The building said to have been built on the south side of the River Wear is translated by Surtees as being a ‘monastery’, by Preest as a ‘church’ and now it is being referred to as a ‘chapel’. Certainly there was a monastery and a church (St Peter’s) at Monkwearmouth and eight years later a monastery and a church (St Paul’s) at Jarrow. An eight year interval for Monkwearmouth monks and stonemasons alike to practice and spread their faith and skills in that neighbourhood before the challenge of Jarrow! |

He goes on to say that he believed that it had been built in the time of the Venerable Bede and that he believed that some of the Chapel stones, in particular the Saxon style headstones, had been utilise by Crowley to build part of his Works.

Indeed he had travelled to Sunderland and met with the late W Bro William Waples, a businessman and eminent freemason of this City whom he wished to consult on the origins of Crowley’s Ironworks. Bro Waples was able to quote information which came from conversations he had previously had with John Meek, the manager of the firm of Richardson and Westgarth which owned the freehold in the 1930s.Presumably, the deeds proved that the building had originally been constructed by Crowley but that these had been destroyed by an air raid in World War 2.

As Flinn had obviously gained access to much that remained of Crowley’s records he may have had sight of any reports made by the men employed on building the ironworks. The information that unsuccessful efforts had been made to preserve the Saxon style head stones, at the time that the building was demolished, could only have come from Mr John Meek.

If the ruined Chapel had existed and time and money had been saved it most certainly would have been reported to Crowley.

The William Waples Collection, Provincial Grand Lodge of Durham, contains four slides of Crowley’s buildings, one depicts the drawing below which appears to partly confirm Flinn’s story and also three photographs of parts of the Ironworks that were built in brick.

Adjacent brick built Ironworks

Crowley’s Office, Sunderland

Crowley’s Ironworks on Low Street, Sunderland.

Reproduced from William Waples’ Library by kind permission of Provincial Grand Lodge of Durham.

This drawing depicts the first floor of a stone building with Saxon style windows, which is obviously part of much larger premises. The Crowley Ironworks office might be a more correct description as Crowley ran all of his business affairs by post from London. His home in London was a great Jacobean Mansion called the Old Palace at Greenwich; Inigo Jones designed the famous staircase in the mansion and this website depicts a painting made of it by the eminent Clarkson Stanfield whose famous father, James Field Stanfield was a member of this lodge.

It is intriguing to think that foreign Hammermen Guild members and Sunderland men worked in Crowley’s building, part of which may have been built with stones from an unknown Anglo Saxon Chapel and that these workmen could have been the catalyst for Freemasonry in Sunderland in general and Sea Captains’ Lodge in particular – intriguing also to think that Ambrose Crowley himself may have been a mason!!

Certainly Lodge of Industry’s own present day literature states:

“Although the origin of the Lodge is shrouded in the mists of antiquity it is quite evident that it was in full operation for some years prior to its Warrant from the Grand Lodge of England which bears the date 24th July, 1735, and it is popularly supposed that Sir Ambrose Crowley (died 1713) who erected the ironworks at Winlaton in 1690 and later at Swalwell, was instrumental in its formation”.

Grand Lodge was founded in 1717 and as the first records of membership are found in the minute book starting in 1723 and as Sir Ambrose died in 1713, there is obviously no record of his membership.

Whether Ambrose Crowley was a mason or not (he was 24 years of age when he first arrived in Sunderland), if he had been instrumental in the formation of the Lodge initially at Winlaton one might wonder if he had previously influenced these same men with the same ambition when they were working at Sunderland?

If so this may well have led to the formation of the Sunderland Time Immemorial Lodge long before 1745, this being the earliest recorded date as noted earlier and it is quite possible that the seeds of masonry were sown, and flourished, somewhere between 1682 and 1745.

W Bro Will Logan of Marquis of Granby Lodge No 124 appeared to be of that opinion.

Comment

In setting out to write this preface it was not envisaged that certain controversial matters would arise but when they did it was felt necessary to fully explore them and obtain as many facts as possible regarding any linkage with Crowley’s Ironworks.

It has been written in narrative form in order to fully explain the origin of the sources used, particularly in the case of the position of the Ironworks and the supposed St Paul’s Chapel.

It is doubtful that the issue of whether or not a St Paul’s Chapel existed from Bede’s time will ever be proven and care has been taken to record all information, whether negative or positive, that could be obtained. However, it is intriguing to think that Michael Flinn, an eminent author/industrial historian of our own times, should feel so sure of his facts that he was able to write down and publish such convincing details, and that our own William Waples should be involved in discussions with him, presumably because Flinn wished to verify the previous existence of the ironworks at that location.

What credence should we attach to Flinn’s “St Paul’s Chapel” story?

Possibly we should look at the local environmental conditions and religious beliefs in Monkwearmouth and Sunderland back in the 7th Century and at the effect on the lives and beliefs of the local people when these stone buildings went up at Monkwearmouth, so adjacent to their wooden, thatched homes.

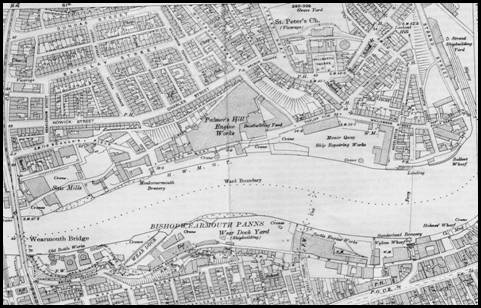

Monks’ Ancient Ferry Crossing

St Peter’s Church, Monkwearmouth, Sunderland, England. 16th September 2006

Map showing the ancient ferry crossing and landing areas over the River Wear

General area on top of high cliffs, above Low Street, where the ‘Chapel’ could have been situated shown thus:-

Any structure built on the supposed Chapel site would be clearly visible from St Peter’s Church!

The old ferry crossing from Bodlewell Lane (Bishopwearmouth) is only a very short walking distance east of the site of Crowley’s Works and of the supposed Chapel.

Indeed it is known that a ferry crossing had existed from the time when the Monkwearmouth Monastery was first built (ancient wooden boats have been retrieved from the river mud) to more recent times when, before the service was discontinued, screw driven ferries such as the Sir Walter Raine and the Vint made the 4/5-minute journey across the river.

Bodlewell, as the name implies, was a well of fresh spring water and Sunderland townsfolk filled up their containers, at the price of a ‘bodle’ or ½ farthing per skeel. Most certainly this and another good well at the bottom of Queen Street will have attracted people to settle in that vicinity with the further attraction of the ferry crossing.

Given the short river crossing and the small distances involved on land, it could be considered more than reasonable, for Benedict Biscop and/or the Venerable Bede to build a Chapel for their workers and the local population on the south side of the River Wear, where it is said that Bede was born.

This to be spiritually served by visiting monastery clerics and be named for St Paul. Certainly, a better proposition than attempting to ferry the south side population to the Church in small boats in all weathers!

(It is interesting to note that Ambrose Crowley built St Mary’s Chapel, to seat 300 worshipers, at Winlaton in 1705 for his foreign workers.)

When looking for a site for the supposed stone built Chapel it would be reasonable to assume that a

prominent position on high ground, close to established settlements and the ferry crossing would be highly desirable.

It so happens that the ground above and just west of Crowley’s Works and just east of where Rowland Burdon’s Iron Bridge was later built (Burdon needed as much height as possible above river level for the tallest ships masts to pass) would be an ideal spot to build such a structure.

This is not to say that a Chapel was built but the local conditions which existed could hardly have been better for this relatively minor project, particularly given their overall desire to spread Roman Christianity (rather than the prevailing Celtic Christianity) throughout the kingdom, and with the Jarrow scheme possibly still several years ahead.

Fig 8

Short walk to Ironworks site Low Street, Bodlewell Lane

Old Ferry Boat landing ahead (5th September 2006)

Further research at the Provincial Grand Lodge of Durham’s “William Waples Library” was carried out with the help of W Bro Tom Coulson, Curator of the Museum and Library and this brought to light a set of documents catalogued as “St Peter’s Church”.

A booklet entitled “St Peter’s Wearmouth” written by the late Robert Hyslop, F.R.Hist.S. F.S.A. (Scot.) proved to be the most informative and pertinent to our researches and contained the information set out below:

1. That the land granted to Benedict Biscop by King Egfrid to build his monastery and church to St Peter on the north side of the River Wear also included land on the south side.

2. That Bede was born and lived on the south side until going into the monastery at the age of seven years.

3. That a ‘tradition’ still persists here (Wearside) that a sister church, dedicated to St Paul was founded by Biscop on the southern bank of the River Wear to complement St Peter’s on the northern bank. He also refers to the possibility of the tradition being created by Malmesbury’s confusion.

4. He speaks of a persistent tradition on Wearside that when Biscop was building his church and monastery on the north bank, he lodged his foreign workmen on the south side and he thinks that it is probable that this gave Malmesbury his authority for his remarks regarding a church dedicated to St Paul on the south side.

5. He feels that further support is given to item 4 when speaking of the ferry across the river known as the “Monks’ Ferry” going from close to St Peter’s Church on the north side to Sunderland on the south side. The rights to the ferry were part of the rights and privileges of the monastery of St Peter and Sunderland Corporation had to pay the sum of £1800 to the Dean and Chapter of Durham when they acquired the ferries. He makes the point of the intimate association of St Peter’s with the south bank of the River Wear.

Summary

With regard to the persistent tradition that Biscop built a sister church ( on the south bank one might wonder when this tradition started, 674 A.D. or 1682 A.D.

If, as Flinn states, Crowley’s workmen uncovered the remains of a chapel and then proceeded to built part of the ironworks with it then surely these actions would not have gone unnoticed by the workmen and seamen along the river bank. The export of coal and the industry of shipbuilding, bottle works etc would have ensured that many people would be aware of what was happening at the time and the fact that the exterior of the building would constantly proclaim its origins, until it was demolished in 1918, would have added much to many “old men’s tales” – the very stuff of traditions!

Parts of the building would have been used for many purposes during its 236 years existence, one such use being that of a public house named ‘The Three Admirals’.

It would seem very doubtful that Flinn, with his academic background and proven scholarship, would have published the account of the St Paul’s Chapel discovery without having some factual basis for it.